Aliyah Bet & Machal Virtual Museum

North American Volunteers In Israel's War of Independence

Pictorial History: Rescue Fleet is Launched

With Holocaust survivors languishing in camps throughout Europe, Americans secretly purchased 12 ships and recruited North American crews to take them through the British naval blockade of Palestine. They were part of the Aliyah Bet (clandestine immigration) movement.

Nazi persecution of Jews in the 1930s was accompanied by increased British restriction on Jewish immigration to Palestine. In response, underground organizations in Palestine chartered small and often-decrepit ships to smuggle Europe’s fleeing Jews to Palestine in defiance of Britain’s strict immigration quota that permitted only 1,250 Jews a month to enter the British mandate. Their work became known as the Aliyah Bet ("Immigration B," the term for the clandestine immigration operation). Their vessels were small, carrying relatively-few passengers. Very few people could be rescued in this fashion after the outbreak of World War II.

The Aliyah Bet organization bought ships, readily available as war surplus in the U.S., of much greater passenger capacity with which to challenge Britain’s restrictive immigration policies. Financed largely by U.S. and Canadian philanthropists, most of those ships later sailed into the teeth of the British naval blockade. The 12 ships were manned by about 240 American and Canadian volunteers in addition to some foreign contract sailors and a handful of Palestinian Jews assigned by Haganah.

In July 1945, a committee of 19 American Jewish leaders was convened in what became known as the “Sonneborn Institute.” Their assignment: to secretly acquire ships for Aliyah Bet and to buy arms for the Haganah. One of those 19 men was Shepard Broad, a prominent Miami attorney, banker, civic leader and philanthropist. Broad quietly enlisted the help of other Miamians and negotiated the purchase of two ships that would attempt to break the British blockade of Palestine with a full load of Holocaust survivors. These ships were the Paducah and the Tradewinds.

The Tradewinds and Paducah, seen at anchor on the Miami River, were typical of the Aliyah Bet ships purchased just after World War II. Designed for crews of from 80 to about 100 sailors, the former naval vessels had been decommissioned and sold as war surplus. Welders and carpenters in European shipyards later tore away the ships’ insides, built enclosed wooden superstructures on the upper decks, installed shelving wherever possible to serve as bunks, and fashioned makeshift latrines to dump human waste into the sea. The Tradewinds ultimately brought 1,414 Polish, Hungarian, Rumanian, and Czech refugees from the coast of Italy to the shores of Palestine in a week-long journey. The Paducah brought 1,388 mostly Rumanian refugees from Burgas, Bulgaria, to Palestine in six days. In both cases, the passengers were 14 times more numerous than the crews the ships were originally designed for.

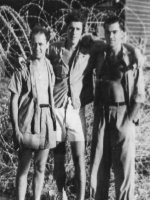

Three Paducah sailors are shown ashore in Biarritz, France, July 1947. Left to right are Louis Ball, New York City; Reuben Schiff, Toronto; and Albert Brownstein, Chicago. A year later, on July 9, 1948, Louis Ball, 26, was killed while serving with a Palmach army unit in the Negev. His best friend, Reuben Schiff, 22, was killed two days later while serving with the same unit. Both are buried near each other in Tel Aviv’s Nachlat Yitzchak cemetery.

Rudy Patzert, 35, the Paducah’s non-Jewish captain, was a highly-experienced World War II Merchant Marine veteran. He was hired to ferry the Paducah to Europe, where he would then turn it over to a Jewish captain. When he arrived in France, he realized he could not abandon the ship or its mission. So he stayed on for its final voyage, and was then interned in Cyprus with his crew.

Moka Limon, 23, was the Haganah emissary on the Paducah. A Palestinian Jew, his duties included everything except the usual duties of the ship’s master, Capt. Patzert. He maintained radio contact with the Haganah, handled logistics ashore, organized the passengers into orderly groups, and supervised food distribution. Moka Limon later became a commander of the Israeli navy.

Paducah Captured at Sea

The Paducah had been shadowed by a growing number of British destroyers when it neared Palestinian waters bearing its new name, Geula (Redemption). Although it was prepared to repel boarding with cans and water hoses, at the last minute orders came from the Haganah not to resist. A Royal Marine boarding party stormed the ships, which was towed into Haifa on October 2, 1947.

For a Short Time, So Near to Home

Hapless Paducah passengers are leaving the captured ship. Over the next few days they boarded caged British transports that then took them to detention camps in Cyprus. Looking on at the left are refugees on the Northland, which had not yet disembarked its passengers. The Northland had been captured and towed to Haifa on the same day. As can be partly seen in this photo, many orphaned children and elderly people were among the Paducah’s passengers. The Paducah’s captain, Rudy Patzert, later recalled that as he looked at the children he saw that “they were looking for nothing at all in the world but a home.” At that moment, he said, “I was committed to their side. What happened to them happened to me, happened to all of us.”

Captured Aliyah Bet crew members were usually held in internment camps in Cyprus that had been built by the British for German prisoners of war in World War II. Crew members disguised as passengers were held in these camps for up to four months before being transferred to further internment in Palestine while waiting for a place in the immigration quota. The Paducah’s captain, Rudy Patzert, is seen here inside a Cyprus camp with two crewmen from the Northland, which was captured the same day as the Paducah. Patzert, left, is shown with Enrico Lopez from Spain, the Northland’s cook, and, right, Howard (Eddie) Edmondson, Northland messman, from New York City. Edmondson was one of two African-Americans who volunteered for Aliyah Bet.

A Phone Call from a Stranger

Paul Kaye was trained as an engineer in the U.S. Navy just at the end of World War II. While working at a record store in the Bronx in March 1947 before entering college, he received a phone call from a stranger: “Do you want to help your people?” He met with the stranger that night. The next morning, the 19-year-old Kaye (in 1947 his name was Kaminetzky) was on a train to Baltimore, where he was to join a crew of 25 other young men assigned to the Tradewinds. Kaye would become 3rd engineer.

A few of Kaye’s crewmates also had Navy or Merchant Marine training in World War II. Some were members of Zionist youth groups. Two were Christians. Since the Tradewinds sailed under a Panamanian flag until it reached Palestinian waters, Kaye needed certification papers from Panama that he was rated as an assistant engineer.

Ready for Shore Leave

The Tradewinds, a former U.S. Revenue Service cutter, sailed to Lisbon for more refitting. Tradewinds shipmates are shown here preparing for shore leave while docked in Lisbon, April 1947. From left to right: Mike Perlstein, Philadelphia; Paul Kaye, New York City; Yehoshua Baharav, a Palestinian kibbutznik and Aliyah Bet representative in Lisbon; Adrian Philips, New York City; Augustine (Duke) Labaczewski, Philadelphia; Irving Rubin, New York City; Marvin Rosenberg, New York City; Harold Katz, Boston; Hugh McDonald, Boston; and Murray Greenfield, New York City. Labaczewski and McDonald were the only Christians aboard, except for the ship’s captain at this point, Frank Scanlon.

The ship then proceeded to Marseilles and Bogliasco, Italy, where it secretly loaded more than 1,400 passengers on two successive nights. After more than a week’s journey east, the Tradewinds was spotted by British aircraft as it approached Palestinian waters. Soon after, British warships appeared.

British Marines Board the Tradewinds

When intercepted by British destroyers, the Tradewinds, newly-renamed Hatikvah (The Hope), resisted by throwing cans at the boarding party. The British marines responded with tear gas and warning shots. Following hand-to-hand fighting, she was captured and towed into Haifa on May 17, 1947. The 26 American crewmen mixed with the passengers and were interned in Cyprus as Jewish “displaced persons” (Kaye was fluent in Yiddish).

Kaye remained a prisoner in Cyprus for two months, then was transferred to the Athlit prison camp near Haifa for another month. In August 1947, three months after the Tradewinds was boarded by British Marines, half of the crew members were still interned. Among them were, left to right, Saul Yellin, Baltimore, Paul Kaye, and Marvin Rosenberg, New York City. Kaye was smuggled out of the camp and sent back to the U.S., where he joined the crew of another ship bound for Palestine. Kaye then served during the War of Independence in Israeli navy unit Shayetet Thirteen (Navy Seals).

The Voyage of Exodus 1947 - How one ship, with a mostly North American crew, helped create a Jewish state.

The President Warfield began life as a Chesapeake Bay excursion liner when it was launched in 1928. It was never designed to traverse the oceans, or to cross swords with a slew of navy destroyers. It did both, and in the end became a legend in Jewish history.

It saw service as the USS President Warfield in World War II, and then was bought as surplus for use in the Aliyah Bet “fleet.” After being refitted in Italy, President Warfield picked up 4,530 Holocaust survivors from Displaced Persons camps in Southern France. Under its new name Exodus 1947, it was intercepted in international waters off the Palestine coast on July 18, 1947, by five Royal Navy destroyers. It refused to obey the order to surrender and was rammed by two destroyers. Passengers and crew threw potatoes and cans of kosher meat at the British Marine boarding party. The British responded with tear gas, fire hoses and lead-weighted truncheons. The second mate of the Exodus and two passengers were killed in the two-hour melee. Exodus 1947 was towed in to Haifa harbor.

To make an example of Exodus 1947, British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin ordered the passengers to be returned to France in three British deportation ships, rather than be interned in Cyprus, as was the usual procedure.

In Port de Bouc, France, the passengers refused to leave their prison ships, and France declined to accept unwilling guests. After a three-week stand-off, the British ships weighed anchor and sailed for the British Occupation Zone of Germany, where the passengers were forcibly taken off in Hamburg and delivered to German Displaced Persons camps.

The passengers of Exodus 1947 made daily headlines.

The spectacle of Holocaust survivors being sent to a country that had authored and carried out the Holocaust enflamed world opinion against England and its Jewish exclusion policy in Palestine. Shortly thereafter, on November 29, 1947, the United Nations voted in favor of a plan to establish a Jewish state, alongside an Arab state, in Palestine.

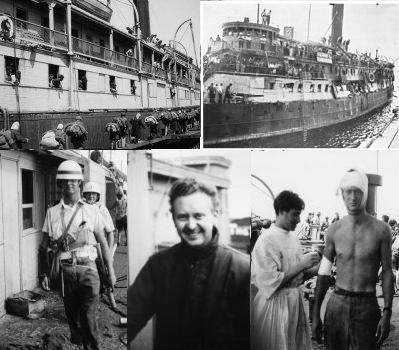

Clockwise: Holocaust survivors from Displaced Persons camps in Germany prepare to board Exodus 1947, then known as President Warfield, in Sete, France. *** Exodus 1947 as it looked when it was towed into Haifa harbor. It received the hole in its side when a destroyer rammed it. Continual sideswiping by British naval craft splintered the length of its sides. *** A nurse bandages Murray Aronoff of New York City, Exodus 1947 seaman wounded in the battle to repel the boarding party of Royal Marines. *** Bill Bernstein, 24, of San Francisco, second mate of the Exodus, was clubbed to death by Royal Marines as he attempted to defend the wheelhouse. He was the first of 40 Americans and Canadians to die on the side of Israel in its fight for independence. *** An officer from the Royal Marines walks down the main deck of the captured ship. The British won the battle. In the final accounting, Exodus 1947 won the war.

Photos courtesy of Bernard Marks

No Luxury on a Pan York Cruise

This view of the Pan York deck gives some idea of a typical voyage of five or more days from Europe to Palestine on an Aliyah Bet ship. The Pan York was one of the two largest ships in the Aliyah Bet fleet. In its first voyage for Aliyah Bet, it transported 7,557 refugees in its holds and decks.On it's second voyage, shown here, it was the first ship to bring large number of women and children to Israel. Some 7,800 passengers were on this voyage.

The large ventilators rising above the deck wafted humid air into the three levels of living quarters in each hold. Since the fetid air in the holds was life-threatening for infants, women with small children had priority to live and sleep on the top deck under a canopy of army blankets (shown in right foreground). Wooden outhouses, such as one in the left foreground, consisted of a long bench with round holes leading directly to the open sea. The woman in the left foreground is bathing her daughter from a salt water basin. The only fresh water on the voyage was strictly rationed for drinking.

The food and drinking ration for each person on the Pan York: one glass of water a day, cheese and crackers for breakfast, broth and crackers for lunch, sardines and crackers for dinner. In a novel about the War of Independence, one author wrote: “After four or five days, [a passenger] would wonder if the smells of the latrines, crushed crackers, sardines, exhausted air, used-up breath, and sweat had permeated one’s skin for all time, as it had permeated the wood and metal of the Pan York.” ("Bring my sons from far," by Ralph Lowenstein, World 1966)

Bunks in the Mala

As was typical in Aliyah Bet ships, there are three tiers of wooden shelves that served as bunks. The shelves were 5 feet, 6 inches deep, with a 26-inch height between shelves. Passengers were assigned a 20-inch wide space on a shelf and slept on the bare wood in their clothes the entire journey.

A Blessing over Shabat Candles

A Holocaust survivor aboard the Mala welcomes the Sabbath on a Friday evening in a hold of the Mala during summer 1948. The woman had boarded the ship from a Displaced Persons camp in Southern France. The candelabra are homemade.

Aliyah Bet Achieves Its Goals

Following World War II, Aliyah Bet had four goals:

Rescue survivors of the Holocaust festering in Displaced Persons camps throughout Europe.

Challenge the right of England to set quotas so low as to essentially bar most of these refugees from entering Palestine, and, more so, challenge the right of England to govern Palestine.

Lay the claim to a Jewish state by significantly increasing the Jewish population of Palestine.

Set a priority to bring in men and women of fighting age who could serve as defenders against the Arab armies that would inevitably attempt to destroy the Jewish presence.

Although just part of a force consisting of Palestinian Jews and volunteers from many nations, the North Americans made a significant impact, particularly considering their small numbers.

Only a handful of American and Canadian Jews were involved in the clandestine purchase of Aliyah Bet ships in North America. Only about 190 American and Canadian volunteers manned the 10 Aliyah Bet ships that would attempt to run the gauntlet of Royal Navy destroyers barring the path to Palestine.

Yet, although 66 Aliyah Bet ships brought a total of 71,534 Jews to Palestine from 1945 to May 15, 1948, the 10 North American ships that ran the British blockade brought in 31,078 of these, or 43.4%.

At the end of World War II, the Jewish population of Palestine was about 500,000. At the beginning of the War of Independence in 1948, it was about 600,000, thanks largely to Aliyah Bet.

Back to A Rescue Fleet is Launched

Back to A Rescue Fleet is Launched